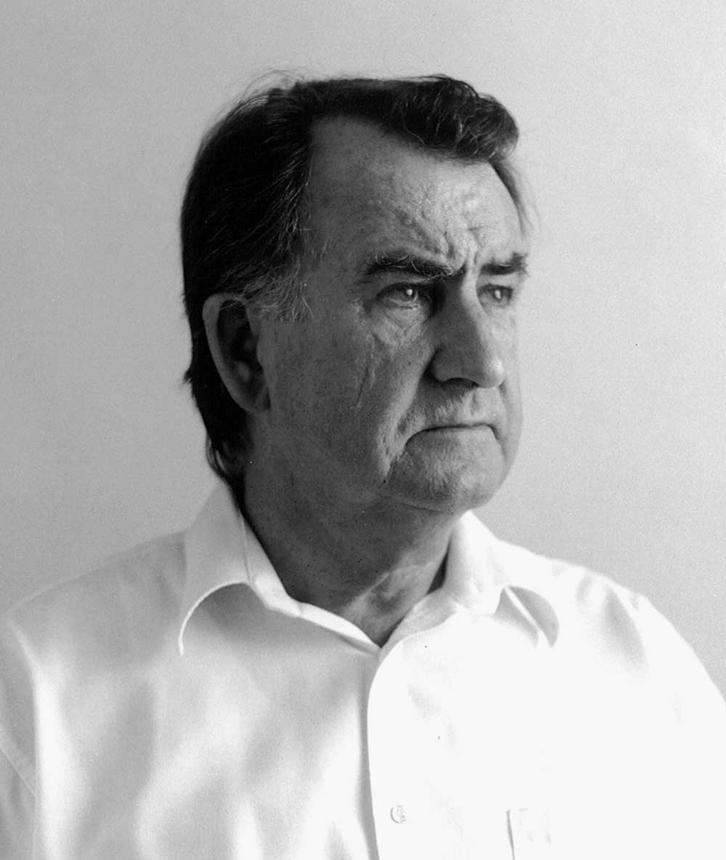

He argues that his books have enabled him to see “connections” and have “revelations” about the world, which for him are “my true reward for writing fiction”. But Murnane’s strong views about literature also reflect his belief that writing is a vital mode for exploring truth. That he has managed to publish such unusual books despite the enormous commercial difficulties of doing so testifies to a persistence that is probably indistinguishable from stubbornness. These complaints might seem curmudgeonly, but Murnane’s unusual perception of the world and refusal to take concepts at face value are what make his fiction unique. He criticises several well-known authors – including Thomas Pynchon, Hermann Broch and László Krasznahorkai – for writing the wrong kind of long sentences. While Murnane expounds upon his love for long sentences, he dislikes when they violate traditional rules of syntax. Murnane’s unusual perception of the world and refusal to take concepts at face value are what make his fiction unique Murnane, at various points, expresses his dislike of scholarly literary criticism, book reviewers, philosophy, neuroscience, cameras, publishers, the way we talk about characters as if they were actual people, and readers’ tendency to conflate their memories of reading a book with the book itself. Though Last Letter is meant to be a final book, it is often more cantankerous than elegiac. These connections are important and meaningful for those who have read Inland, but they are hardly an explication of authorial intent. His discussion of his 1988 novel Inland turns from Murnane’s love for the sonorities of the Hungarian language (which he taught himself) to a discussion of Proust.

They ruminate instead on unexpected connections between books, ideas and the specific life experiences that informed his writing. The essays in Last Letter are neither literary criticism nor memoir. He reveals that he published a still-unknown book of poetry under a pseudonym before he began writing novels. He also “sometimes regrets” the title The Plains, which his publishers suggested over his preferred Landscape with Darkness and Mirage. His most celebrated work, 1982’s The Plains, started as “a sort of florid descant accompanying a conventional narrative” in a much longer work, entitled The Only Adam. He often discusses differences between the manuscripts he wrote and the books that resulted from them. While this might seem strange, Murnane notes that he had “previously read none of my books in its published form”.

The idea for the book came to Murnane during lockdown in the small Victorian town of Goroke in 2020, when he decided to read his books “in the order of their publication” and write a “report of my experience as a reader of each book”. Now, Murnane has published another final book, Last Letter to a Reader.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)